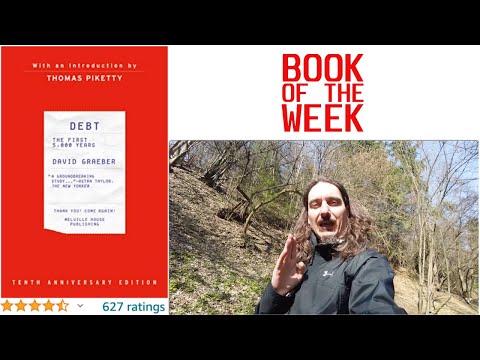

Debt: The First 5000 Years by David Graeber Book Review

Hello

and HAPPY DAY!

How does slowing down sound to you today?

Would you like to reduce the noise for just

a bit?

Are you ready to make a choice and decide

to listen?

My name is Igor, SF Walker.

I am here to remind people to slow down.

To reduce the noise.

To walk their lives into a natural flow.

Welcome back to the Book of the Week series.

Every week as I read another amazing title,

I share it with the world.

Today we look at: Debt The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber.

In this video we will look at what is debt,

where does the language of debt come from

and how it applies to everyday life.

History of debt and debt through history.

Is this a question of morality or is it actually

something evil.

Are we actually in debt to the universe and

life itself?

Looking at the links between religion, payment

and the mediation of the sacred and profane

realms by “money.”

How is it that moral obligations between people

come to be thought of as debts and as a result,

end up justifying behavior that would otherwise

seem utterly immoral?

Stick around till the end, as I will

with you a way to explore the mystery of yourself

and your personality, how to find out why

you do the things you do, what are the hidden

motivators behind the scenes, these innate

human needs we are sometimes not even consciously

aware of.

debt • noun

1 a sum of money owed.

2 the state of owing money.

3 a feeling of gratitude for a favour or service.

— Oxford English Dictionary

If you owe the bank a hundred thousand dollars,

the bank owns you.

If you owe the bank a hundred million dollars,

you own the bank.

— American Proverb

Actually, the remarkable thing about the statement

“one has to pay one’s debts” is that

even according to standard economic theory,

it isn’t true.

A lender is supposed to accept a certain degree

of risk.

If all loans, no matter how idiotic, were

still retrievable—if there were no bankruptcy

laws, for instance—the results would be

disastrous.

Sounds like common sense, but the funny thing

is, economically, that’s not how loans are

actually supposed to work.

Financial institutions are supposed to be

ways of directing resources toward profitable

investments.

If a bank were guaranteed to get its money

back, plus interest, no matter what it did,

the whole system wouldn’t work.

The very fact that we don’t know what debt

is, the very flexibility of the concept, is

the basis of its power.

If history shows anything, it is that there’s

no better way to justify relations founded

on violence, to make such relations seem moral,

than by reframing them in the language of

debt—above all, because it immediately makes

it seem that it’s the victim who’s doing

something wrong.

Mafiosi understand this.

So do the commanders of conquering armies.

For thousands of years, violent men have been

able to tell their victims that those victims

owe them something.

If nothing else, they “owe them their lives”

because they haven’t been killed.

For the last five thousand years, with remarkable

regularity, popular insurrections have begun

the same way: with the ritual destruction

of the debt records—tablets, papyri, ledgers,

whatever form they might have taken in any

particular time and place.

After that, rebels usually go after the records

of landholding and tax assessments.

As the great classicist Moses Finley often

liked to say, in the ancient world, all revolutionary

movements had a single program: “Cancel

the debts and redistribute the land.”

Terms like “reckoning” or “redemption”

are only the most obvious, since they’re

taken directly from the language of ancient

finance.

In a larger sense, the same can be said of

“guilt,” “freedom,” “forgiveness,”

and even “sin.”

Arguments about who really owes what to whom

have played a central role in shaping our

basic vocabulary of right and wrong.

After all, to argue with the king, one has

to use the king’s language, whether or not

the initial premises make sense.

If one looks at the history of debt, then,

what one discovers first of all is profound

moral confusion.

Majority of human beings hold simultaneously

that (1) paying back money one has borrowed

is a simple matter of morality, and (2) anyone

in the habit of lending money is evil.

What, precisely, does it mean to say that

our sense of morality and justice is reduced

to the language of a business deal?

What does it mean when we reduce moral obligations

to debts?

What changes when the one turns into the other?

And how do we speak about them when our language

has been so shaped by the market?

Economists generally speak of three functions

of money: medium of exchange, unit of account,

and store of value.

All economic textbooks treat the first as

primary.

Human nature does not drive us to “truck

and barter.”

Rather, it ensures that we are always creating

symbols—such as money itself.

This is how we come to see ourselves in a

cosmos surrounded by invisible forces; as

in debt to the universe.

The “primordial debt,” writes British

sociologist Geoffrey Ingham, “is that owed

by the living to the continuity and durability

of the society that secures their individual

existence.”

In this sense it is not just criminals who

owe a “debt to society”—we are all,

in a certain sense, guilty, even criminals.

In all Indo-European languages, words for

“debt” are synonymous with those for “sin”

or “guilt,” illustrating the links between

religion, payment and the mediation of the

sacred and profane realms by “money.”

Perhaps what the authors of the Brahmanas

were really demonstrating was that, in the

final analysis, our relation with the cosmos

is ultimately nothing like a commercial transaction,

nor could it be.

That is because commercial transactions imply

both equality and separation.

These examples are all about overcoming separation:

you are free from your debt to your ancestors

when you become an ancestor; you are free

from your debt to the sages when you become

a sage, you are free from your debt to humanity

when you act with humanity.

All the more so if one is speaking of the

universe.

If you cannot bargain with the gods because

they already have everything, then you certainly

cannot bargain with the universe, because

the universe is everything— and that everything

necessarily includes yourself.

One could in fact interpret this that the

only way of “freeing oneself” from the

debt was not literally repaying debts, but

rather showing that these debts do not exist

because one is not in fact separate to begin

with, and hence that the very notion of canceling

the debt and achieving a separate, autonomous

existence was ridiculous from the start.

This is a great trap of the twentieth century:

on one side is the logic of the market, where

we like to imagine we all start out as individuals

who don’t owe each other anything.

On the other is the logic of the state, where

we all begin with a debt we can never truly

pay.

We are constantly told that they are opposites

and that between them they contain the only

real human possibilities.

But it’s a false dichotomy.

States created markets.

Markets require states.

Neither could continue without the other,

at least, in anything like the forms we would

recognize today.

Markets aren’t real.

They are mathematical models, created by imagining

a self-contained world where everyone has

exactly the same motivation and the same knowledge

and is engaged in the same self-interested

calculating exchange.

Economists are aware that reality is always

more complicated; but they are also aware

that to come up with a mathematical model,

one always has to make the world into a bit

of a cartoon.

There’s nothing wrong with this.

The problem comes when it enables some (often

these same economists) to declare that anyone

who ignores the dictates of the market shall

surely be punished—or that since we live

in a market system, everything (except government

interference) is based on principles of justice:

that our economic system is one vast network

of reciprocal relations in which, in the end,

the accounts balance and all debts are paid.

How is it that moral obligations between people

come to be thought of as debts and as a result,

end up justifying behavior that would otherwise

seem utterly immoral?

Answer: by making a distinction between commercial

economies and “human economies”—that

is, those where money acts primarily as a

social currency, to create, maintain, or sever

relations between people rather than to purchase

things.

As Rospabé so cogently demonstrated, it is

the peculiar quality of such social currencies

that they are never quite equivalent to people.

If anything, they are a constant reminder

that human beings can never be equivalent

to anything—even, ultimately, to one another.

Historically, war, states, and markets all

tend to feed off one another.

Conquest leads to taxes.

Taxes tend to be ways to create markets, which

are convenient for soldiers and administrators.

In the specific case of Mesopotamia, (origins

of patriarchy) all of this took on a complicated

relation to an explosion of debt that threatened

to turn all human relations—and by extension,

women’s bodies—into potential commodities.

At the same time, it created a horrified reaction

on the part of the (male) winners of the economic

game, who over time felt forced to go to greater

and greater lengths to make clear that their

women could in no sense be bought or sold.

Freedom is the natural faculty to do whatever

one wishes that is not prevented by force

or law.

Slavery is an institution according to the

law of nations whereby one person becomes

private property (dominium) of another, contrary

to nature.

Government was essentially a contract, a kind

of business arrangement, whereby citizens

had voluntarily given up some of their natural

liberties to the sovereign.

Finally, similar ideas have become the basis

of that most basic, dominant institution of

our present economic life: wage labor, which

is, effectively, the renting of our freedom

in the same way that slavery can be conceived

as its sale.

It’s not only our freedoms that we own;

the same logic has come to be applied even

to our own bodies, which are treated, in such

formulations, as really no different than

houses, cars, or furniture.

We own ourselves, therefore outsiders have

no right to trespass on us.

Debt had two possible outcomes.

The first was that the aristocrats could win,

and the poor remain “slaves of the rich”—which

in practice meant that most people would end

up clients of some wealthy patron.

Such states were generally militarily ineffective.

The second was that popular factions could

prevail, institute the usual popular program

of redistribution of lands and safeguards

against debt peonage, and thus create the

basis for a class of free farmers whose children

would, in turn, be free to spend much of their

time training for war.

The modern banking system manufactures money

out of nothing.

The process is perhaps the most astounding

piece of sleight of hand that was ever invented.

Banking was conceived in iniquity and born

in sin.

Bankers own the earth; take it away from them,

but leave them with the power to create credit,

and with the stroke of a pen they will create

enough money to buy it back again.

If you wish to remain slaves of Bankers, and

pay the cost of your own slavery, let them

continue to create deposits.

We could end by putting in a good word for

the non-industrious poor.

At least they aren’t hurting anyone.

Insofar as the time they are taking off from

work is being spent with friends and family,

enjoying and caring for those they love, they’re

probably improving the world more than we

acknowledge.

Maybe we should think of them as pioneers

of a new economic order that would not share

our current one’s penchant for self-annihilation.

It seems to me that we are long overdue for

some kind of Biblical-style Jubilee: one that

would affect both international debt and consumer

debt.

It would be salutary not just because it would

relieve so much genuine human suffering, but

also because it would be our way of reminding

ourselves that money is not ineffable, that

paying one’s debts is not the essence of

morality, that all these things are human

arrangements and that if democracy is to mean

anything, it is the ability to all agree to

arrange things in a different way.

What is a debt, anyway?

A debt is just the perversion of a promise.

It is a promise corrupted by both math and

violence.

If freedom (real freedom) is the ability to

make friends, then it is also, necessarily,

the ability to make real promises.

What sorts of promises might genuinely free

men and women make to one another?

At this point, we can’t even say.

It’s more a question of how we can get to

a place that will allow us to find out.

And the first step in that journey, in turn,

is to accept that in the largest scheme of

things, just as no one has the right to tell

us our true value, no one has the right to

tell us what we truly owe.

And there you have it.

Please do help out, its easy, simply like

this video so more people can enjoy it.

Share it too and spread the word.

Leave a comment and share your thoughts.

Subscribe to my channel and stay up to date.

Link to this book is in the description below.

Buy it.

Read.

Never stop learning.

Especially learning about yourself and nature.

So gift yourself by taking the free human

needs test on my website and find out what

actually motives you, what innate human need

is driving all of your decisions and your

behavior.

If you feel you are ready to improve your

self-awareness, social awareness, self-management

and relationship management even further,

do check out my Master of Life Awareness program.

Links are in the description below.

Thank you

Love&Respect