Your Body is Your Brain by Amanda Blake Book Review Leverage Your Somatic Intelligence, Find Purpose

Hello and HAPPY DAY!

How does slowing down sound to you today?

Would you like to reduce the noise for just

a bit?

Are you ready to make a choice and decide

to listen?

My name is Igor, SF Walker.

I am here to remind people to slow down.

To reduce the noise.

To walk their lives into a natural flow.

Welcome back to the Book of the Week series.

Every week as I read another amazing title,

I share it with the world.

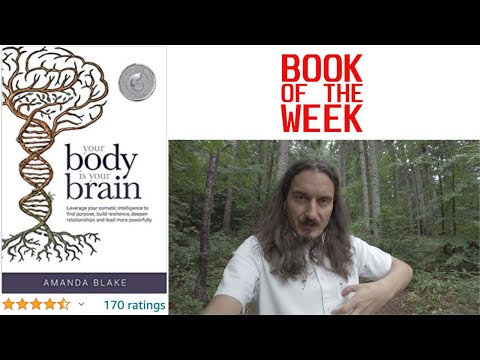

Today we look at: Your Body is Your Brain:

Leverage Your Somatic Intelligence to Find

Purpose, Build Resilience, Deepen Relationships

and Lead More Powerfully by Amanda Blake

In this video we look at practical actions

that generate reliable results, grounded in

research from over twenty-five different scientific

disciplines.

We peer through multiple lenses at a central

question: What role does the body play in

our success and satisfaction in life?

And might it be more influential than we’ve

ever imagined?

Stick around till the end, I will share with

you some tools I have and use that will help

you tremendously in this game of life.

Discover a way to find out what actually motives

you, what innate

of your decisions and your behavior.

I will share some tools to improve your self-awareness,

social awareness, self-management and relationship

management

We can’t see ultraviolet light, for example,

but bees can.

That doesn’t mean the light waves aren’t

there when we’re looking.

It simply means that they’re invisible to

our eyes.

In other words, our biological apparatus filters

our perceptions.

We don’t see the world as it is, so much

as we see the world as we are.

It turns out this is as true of our moods

and our relationships as it is of color and

light.

Our bodies, our brains, and even our behavior

take shape—quite literally—in response

to our life experiences.

And that biobehavioral shape ultimately affects

the possibilities we see, the options we choose,

and the actions we take.

This is true for every single one of us, not

just the color blind.

Our brains have been finely honed over millions

of years of evolution to carefully attend

to our social and emotional environment, and

to quickly adopt and always remember behaviors

that help us optimize access to three essential

nutrients: safety, connection, and respect.

The earthworm embodies one of nature’s earliest

attempts at a nervous system, with its small

clusters of nerve cells strung like beads

down its long, wriggly body.

Nature evolved a centralized group of nerve

cells that clustered at one end of the spine:

the brainstem.

Now popularly known as the “lizard brain,”

the brainstem gives reptiles (and anyone else

with a brainstem, including us) many more

behavioral responses to threat.

As mammals came along and began giving live

birth, a new evolutionary pressure emerged,

offspring needed a way to communicate their

needs to caregivers.

For this, nature evolved the subcortical limbic

system—often referred to as the “emotional

brain”—a collection of structures that

turn the symphony of body language, vocalization,

and facial expression into meaningful communication.

The most recently evolved layer of the brain,

the cerebral cortex, has greater neural density

in species that live in social groups: dolphins,

whales, monkeys, elephants, humans.

Biologists postulate that this layer of the

brain evolved in part to help social species

successfully navigate the dizzying complexities

of living in a troop, tribe, or community.

The brain evolved to optimize access to safety

(brainstem), connection (limbic system), and

social status, or what we might refer to as

dignity or respect (cerebral cortex).

Anything that stores information requires

a physical record, whether that’s zeros

and ones on a microchip, hieroglyphics on

stone, ink on a page, or grooves on vinyl.

Your implicit emotional memories have a physical

record, too.

They’re stored in the neuromuscular patterns

that affect virtually every tissue in your

body.

This occurs in part through a process called

armoring.

Physical contraction to either stifle or fend

off unwanted emotion.

Process goes on with our social and emotional

development.

As our bodies take shape in response to our

environment, our biological lens gets tuned

to a particular way of seeing the world and

being in it.

Certain kinds of emotional responses, interpretations,

and relational defaults get wired into our

body.

This makes some actions second nature, and

others much more difficult.

We could even say they’re invisible to us,

at times.

Biology is perception.

We don’t see the world as it is—we see

the world as we are.

As our bodies are “tuned” to certain emotional

and relational ways of being, that affects

both the options and possibilities that we

see, as well as the actions and behaviors

that are easily available.

Your repeated gestures and your physical structure

affect your mood, and your mood affects your

actions.

And your actions affect both your relationships

and your results, in virtually every area

of your life.

Three primary evolutionary pressures drove

the development of the brain: the need for

physical safety, the need for emotional communication,

and the need for social navigation.

Your brain is your social and emotional sense

organ.

The brain takes physical shape as it learns

behaviors that optimize access to three essential

nutrients: safety, connection, and respect.

Your brain is distributed throughout your

entire body, and your body also subtly takes

shape in response to your life experience.

Through the unconscious and highly adaptive

processes of implicit memory and armoring,

you put successful behaviors on neuromuscular

autopilot.

This can create biobehavioral blind spots

that are exceedingly resistant to change.

Your body is a lens of perception.

Everything you perceive is filtered through

the medium of your body.

So those blind spots affect the possibilities

you see.

Your body is an instrument of action.

Every single action you take involves your

body.

So your biobehavioral blind spots also affect

your actions.

The bottom line: Your body is a finely tuned

social and emotional sense organ shaped by

your life experience.

And that shaping affects both the possibilities

you see and the actions you take.

Your results in almost every area of life

are subtly but inescapably influenced by the

characteristics and qualities you’ve come

to embody.

Whereas conceptual self-awareness takes you

anywhere in time, embodied self-awareness

takes you to this moment in time.

Because sensation can only be experienced

in the present moment, embodied self-awareness

brings you home to the only moment you ever

have for sure, which is right now.

Our brains take shape based on where we repeatedly

rest our attention.

So you would be wise to pay attention to,

well what you’re doing with your attention.

Fundamentally, emotional intelligence is the

ability to be aware of and manage your own

moods, and to take action on your own behalf.

Social intelligence relies on those same skills

of awareness and action, as applied to others.

It’s the ability to accurately pick up on

others’ emotions and to rely on that understanding

in order to skillfully take action as a coordinated

group.

And somatic intelligence—the ability to

discern subtle nuances between different bodily

states, moods, and thought patterns and to

respond effectively to those nuances—is

the underpinning of both social and emotional

intelligence.

Most vagal nerve cells—between 80 and 90

percent—send interoceptive signals from

the trunk to the head.

In other words, your heart is constantly talking

to your brain.

This anatomy makes the vagus nerve and the

organs it’s connected to—particularly

the heart and the gut—key players in the

social and emotional sense organ that is your

body.

The heart communicates with the brain in other

ways, too.

It is the rhythmic leader of the entire body:

Breathing, brainwaves, and even blink rate

are all affected by the pace set by your heart.

The startle of a near-miss car accident and

the subsequent heartpounding recovery sends

rhythmic and electrochemical signals to the

brain, sounding the severe-threat alarm.

In nanoseconds your brain has already coordinated

a complete physical response.

A small cluster of cells inside the amygdala

fire six to eight milliseconds after each

heartbeat.

In other words, in addition to taking its

cues from the surrounding world, oftentimes

your brain takes cues about safety and danger

directly from the pace of your heart.

So if your heart is beating slowly or expanding

with tenderness, your brain gets that message,

too.

Evoking sustained commitment requires a strong

synthesis of conceptual and embodied self-awareness.

It’s vital to know where you’re headed

and why: to articulate a clear vision of the

future and its importance.

It’s equally vital to connect to your felt

sense of care, and then to consistently mobilize

that care into action.

This movement into action—and it is a physical

movement, not an intellectual idea—is precisely

what distinguishes true commitment from otherwise

flimsy intentions.

Lasting change requires clarity + care + a

choice + commitment

Even when you’re clear about your vision

and deeply committed to bringing it to life,

doing so depends on the personal and interpersonal

qualities effective leaders share.

This is true in your personal life just as

much as your professional life.

Once you know where you want to go, you need

the courage to take the first step, and then

to continue stepping out.

You need the composure to handle inevitable

rough waters without calling it quits.

And you need the confidence and credibility

to successfully engage others and enlist support.

In other words, you need to build the personal

qualities that support purposeful action.

Self-mastery is the core skill that supports

the inner qualities.

Sometimes called self-regulation or emotional

regulation, this skill is what enables you

to face challenges with resilience, equanimity,

and authority.

It is the “action” part of emotional intelligence,

and it is essential to navigating just about

any difficult terrain.

The basic somatic competency that undergirds

resilience, emotional regulation, and self-mastery

is the capacity to center yourself.

Centering is about building your capacity

to tolerate strong sensations without having

to automatically act to make the discomfort

disappear.

It’s about actively returning yourself to

a state of psychophysiological coherence when

you are frazzled.

It’s about adjusting and aligning your posture

so that the maximum amount of breath and energy

can reach every nook and cranny of your body,

so you are well positioned to use all of that

energy to your advantage.

And as you’ll come to see, it’s about

far, far more than taking a deep breath and

counting to ten.

Stress is fundamentally a physiological event.

Under pressure or perceived threat, the body

is flooded with adrenaline, cortisol, and

other hormones.

The sympathetic branch of the nervous system

kicks in automatically, increasing heart rate

and breathing, slowing digestion, and shunting

blood to muscles, readying us for fight or

flight.

All of this is well known, but it’s hardly

the whole story.

Neuroception—a perceptual process that distinguishes

between safety and danger by combining exteroceptive

perception of the environment with interoceptive

perception of one’s visceral state.

Immobilization is one of our most ancient

and reliable responses to being attacked.

Oftentimes not aggravating an aggressor is

the smartest way to stay safe.

Dr. Amy Cuddy’s research and flagship experiment

demonstrated that sitting or standing in a

powerful posture for as little as one minute

generates measurable changes in physiology,

psychology, and behavior.

Experimenters asked participants to lean back

into the time-honored “boss’s office”

pose—feet propped up on the desk with hands

interlaced behind their head—or to stand

with their hands on their hips in a similarly

powerful pose.

When tested before and after these brief interventions,

both men and women showed an increase in testosterone

and a decrease in the stress hormone cortisol.

Participants’ sense of their own efficacy

increased.

And they became more willing to take calculated

risks, such as seeking a potential payoff

in a simple gambling task.

The control group spent one minute in each

of several closed postures: arms crossed,

head dropped, limbs pulled in close.

These participants showed the opposite results

on all measures.

Instead of faking it till you make it, practice

it until it’s embodied.

There’s nothing fake about it.

Dialing up awareness of body, breath, thoughts,

and emotions—without having to immediately

respond—is one of the best ways to restore

psychophisological coherence to the body.

Call this the physiology of resilience.

Even if your typical day doesn’t require

you to find the courage to face down lifethreatening

danger, courage has a place in your life.

Those moments where your life calls you to

something new but scary: a move across country,

a career change, a second marriage, a first

date.

Courage can be invoked at any level of fear,

and the process is the same.

Your body responds with a neuroceptive assessment

of safety and danger, and if there is some

visceral detection of potential threat, your

stress systems will wisely gear up for the

challenge.

If stress is a physiological response, so

too is resilience.

And so, then, is courage.

The word courage derives from the French word

coeur, meaning “heart.”

Have heart, courage asks of us.

Take action on what really matters.

Courage doesn’t offer false reassurances

that things are going to turn out okay.

It simply supports you in making a bold move

despite the risks and potential consequences.

When the stakes get higher, you need more

powerful tools.

How you stand impacts courage: The psoas muscles

that control pelvic tilt also affect your

capacity to relax and stay calm, cool, and

collected.

Because these muscles attach on the same vertebra

as the diaphragm, they also affect how you

breathe.

And the muscles you use to breathe are the

same muscles you use to stay upright.

With every breath, you subtly challenge your

balance and postural stability.

Shallow breathing is associated with emotions

such as fear and surprise, this habitual breath

pattern propagates a persistent message of

mild anxiety throughout your entire system.

You breathe at least nine hundred times an

hour.

That’s over 21,000 times a day and more

than 150,000 times a week.

Only your heart muscle moves more.

So you have ample opportunity to develop the

muscle memory that makes a particular breath

pattern automatic.

And because the way you breathe is tightly

linked to the way you move, how you habitually

stand is going to affect your breath.

Composure is not about getting rid of the

nerves.

Nice as that may sound, sometimes it’s not

possible.

Rather, like courage, composure is about being

able to tolerate all the strong sensations

that go along with making a big, important

move.

It’s about consciously feeling all of the

intensity and physical discomfort while aligning

yourself in such a way that those sensations

can move through you without getting stuck

in a swirling whirlpool of anxiety.

It’s about using your breath as best you

can and choosing to take action from your

commitment rather than your fear.

This is what courage and composure really

feel like.

It’s not always comfortable.

In fact, it rarely is.

And yet it’s often the one thing that makes

all the difference in meeting challenging

circumstances.

We know that stress is a physiological response

to pressure.

And if stress is physiological, then your

capacity to recover from stress must be, too.

You can’t always talk yourself out of anxiety.

And actually, that’s fantastic news.

Because just as you can build bigger biceps

or stronger abs, you can build the muscle

memory that makes composure and resilience

easier to access.

Learn to tolerate intense sensations, get

your hips underneath you, and open your belly

and chest to more breath.

All of this allows you to regulate wild emotions

and face the slings and arrows of life with

a more relaxed and settled stance, cultivating

a psychophysiological coherence that not only

improves your mood, but also improves your

performance.

With practice you can make these ways of inhabiting

your body second nature, so that reaching

for courage and composure becomes as easy

and automatic as getting a spoon to your mouth.

And therein lies the magic.

Because when you embody composure, you can

contend with a whole host of things that previously

seemed difficult or impossible.

And that brings success more easily within

reach.

The courage, composure, and confidence create

a stable foundation for credibility.

Because it’s rarely comfortable to reveal

the foibles that make you most relatable.

But doing so in a way that establishes both

your confidence and your competence is precisely

what’s required to build trust.

Centered-yet-vulnerable truth-telling is also

the glue that sustains many a deep friendship

and happy marriage.

It’s the unspoken safety net that allows

a recalcitrant teenager to open up to a parent

when most in need of guidance.

It’s the satisfaction and relief that comes

from being real; from not having to hide your

uncertainties, your frailties, your failures,

and your humanity.

And because we all have our own all-toohuman

stories, authenticity can be deeply connecting,

embodied self-awareness supports meaningful

connections and deeper empathy.

Unconscious tension functions largely the

same way conscious tension does; the difference

is that you’re not aware of it and you can’t

relax it at will.

And unfortunately, unconscious tension interferes

with presence.

If presence is predicated on feeling sensations,

then presence becomes next to impossible when

chronic tension or prolonged absence of attention

makes you numb to sensation.

And I guarantee you’re holding unconscious

tension.

We all do.

To relax it, you first need to become aware

of it.

And there is no better way to do this than

with the direct connection of touch.

Slow down, shut up, and feel.

This skill of feeling, so essential to connection,

is something few of us are actually taught

how to do.

We all have mirror neurons that help us model

the behavior of others.

But here’s the kicker—these mirror neurons

don’t act in isolation.

Situated in the motor cortex, mirror neurons

fire when we hear or see someone else move.

They also connect to neurons in our emotional

brain (specifically the insula, a part of

the brain involved in self-awareness) and

to motor neurons throughout the body.

In other words, we use our entire bodies to

make sense of other people.

Thanks to mirror neurons—and the way they

hook into your entire distributed nervous

system—when someone picks up a cup, you

can instantly sense whether she’s about

to calmly take a sip or angrily throw it across

the room.

This nonconceptual modeling process is one

of the primary ways you make sense of other

people.

Mirror neurons tell you about action, emotion,

and intention as expressed through another’s

body and read through your own felt sense.

Essentially, you get insight into others by

automatically and unconsciously answering

the question “How would it feel to me if

I were to make that move?”

You perceive others through the very same

neural networks that you yourself use to take

the same action, employ the same tone of voice,

or make the same expression.

Own range is limited, your capacity to “get

it” when others are experiencing something

unfamiliar is truncated.

It turns out the less you can feel yourself,

the less you can “suffer with,” or have

compassion for, another.

Conversely, the more access you have to your

own sensations and emotions, the more empathy

and compassion you can access.

We feel with by feeling ourselves.

To begin with, SENSE more.

Pay deliberate attention to your sensations.

Familiarize yourself with their subtle nuances.

Learn to sense every part of your body, from

the inside.

Be aware of how you’re standing, sitting,

moving.

Connect to your feeling of care—truly experience

caring about who and what you love.

What’s important for you to care for and

protect in this situation?

Also, CENTER.

Cultivate the capacity to experience intense

sensations without having to immediately react

to them.

Instead of letting your discomfort drive you,

learn how to return yourself to a state of

psychophysiological coherence, so that you

can access your full intelligence under pressure.

Build PRESENCE.

Stay connected to those you’re in conflict

with.

Respect their inherent worth and dignity as

much as you can.

Build trust and rapport.

When people feel seen and heard, they are

naturally more cooperative.

GALVANIZE others.

When you’ve mastered your own internal state

and connected with the other person to the

degree that you’re able, then it’s time

to take action.

Embody the skill of making a clear request,

rather than stammering it out.

Build the capacity to say no, if that’s

something that’s difficult for you.

The more you sense yourself, the more you

immediately, easily, and automatically empathize

with others.

This connection is simply a neurobiological

reality; it is how our psychobiology is designed.

The more you connect to your own felt sense

of love, care, and desire to make a positive

difference, the more powerfully and effectively

you can take action.

The more you center yourself and get present

in the face of challenge, the better you become

at communicating, leading teams, and resolving

conflict.

These qualities and capabilities are the hallmark

of powerful, trusted, and effective leadership.

Musicians, athletes, actors, and artists of

every stripe know this truth: The body only

learns through practice.

Most artists—including artists of athleticism—spend

upwards of 80 percent of their time in practice

or rehearsal.

Reading a book or attending an afternoon workshop

is the equivalent of going to the gym and

learning how to do sit-ups.

You can’t walk out of that initial session

and say, “Check it out, now I have abs!”

If you want six-pack abs, you’re going to

have to do those sit-ups again and again,

first to build and then to maintain the body

you want.

Embodied practice creates durable change,

because it rewires your entire neuromusculature

and creates new embodied patterns that affect

your day-to-day actions.

If you take the time to build the muscle memory

for key personal and interpersonal qualities

such as the ability to maintain composure,

access compassion, resolve conflict, and act

from care, those qualities become accessible

to you for the rest of your life.

And there you have it: Your Body is Your Brain.

Please do help out, its easy, simply like

this video so more people can enjoy it.

Share it too and spread the word.

Leave a comment and share your thoughts.

Subscribe to my channel and stay up to date.

Link to this book is in the description below.

Buy it.

Read.

Never stop learning.

Especially learning about yourself and nature.

So gift yourself by taking the free human

needs test on my website and find out what

actually motives you, what innate human need

is driving all of your decisions and your

behavior.

If you feel you are ready to improve your

self-awareness, social awareness, self-management

and relationship management even further,

do check out my Master of Life Awareness program.

Links are in the description below.

Thank you Love&Respect